Slow to load...but worth it!

|

Caption: |

From Centralia (Ill.) Sentinel – Sunday, January 27, 1985

The

Alligator: Dahlgren’s Grand Hotel

By

Judith Joy

New York has its Waldorf, London its Ritz and Savoy; but in Dahlgren the Alligator Hotel was the place to stay. In the early part of the century, when railroad passenger service flourished, every small town of any size had a hotel of some fort; but the Alligator was the only one with a pool of real, live gators in the front yard.

Every spring hotel proprietor, Charley Goin, would send off to Jacksonville,

Fla. for a fresh supply of alligators. In

the front of the hotel, carefully fenced from in from the public, he built an

ornamental fountain and pool in which the gators were kept.

“The biggest one we ever had was more than six feet,” says Lucille

Garrison of Mt. Vernon, whose parents owned the hotel.

Mrs.

Garrison, who is 82, recalls that each fall her father brought the alligators

into the hotel for the winter. The

alligators were kept out of sight in a storage area under the stairway that led

to the second floor. The alligators

became torpid during the cold weather and two or three times each winter Goin

would bring them out and place them in front of the stove to try to revive them.

“It

was so cold and he could never wake them up,” says Mrs. Garrison.

“He’d think they come out of it, but they never did, they’d die,

and he’d have to get new alligators each year.”

The

alligators were fed with pieces of meat placed on sticks, so that no one had to

get too close. “One time recalls

Mrs. Garrison, “the alligators escaped from the pen and dad told us not tell

anyone because people would be scared to death all over town.”

Two of the escapees were found in the pond where baptisms were held, but

the others remained at large.

The

Alligator Hotel was built in 1908 and was the pride of Dahlgren.

It replaced an earlier frame building which Goin had moved to an

adjoining site. The foundation of

the new hotel was built of sandstone, which was quarried about three miles from

town and hauled to the site by a team of mules, which Goin hired for the

occasion. The hotel had three

stories, but the upper floor was never finished.

On the first floor was the office, a kitchen, dining room, a parlor and a

big sample room which ran the entire length of the building.

When

the drummers or traveling salesmen came to town they would spread their samples

on the table and the proprietors of the country stores would come into Dahlgren

to select yard goods, clothing, tools and all the sundries they needed to stock

their general stores. In later

years, when the road got better and salesmen called on their customers, the big

room was used to store caskets. Charley

Goin and his brother-in-law, Wesley Hart, were partners in an undertaking

business and would make house calls to lay out the dead. Since they didn’t do embalming, the undertaker would have

to come from McLeansboro if the family wanted the deceased embalmed.

When Goin’s 10-year-old daughter (son?), John Owen, died in the flue

epidemic, he gave up the undertaking business completely.

“He just couldn’t do it anymore,” says Mrs. Garrison.

There

were twelve bedrooms the second floor, one bathroom and a separate toilet for

the men and another for the ladies. In

addition, each of the rooms had a pitcher and washbowl, plus a chamber pot.

The family also lived on the second floor, sharing the sanitary

facilities with the guests.

The

traveling men were the hotel’s main clients, and since there were no paved

roads they all used the L&N Railroad. Rail

was the main means of travel in those days and there were five passenger trains

daily that came through Dahlgren. The trains were met by a drayman who was unkindly referred to

as “Dummy” by everyone because he was a deaf mute. Dummy also suffered from Goitre, then a common affliction;

but he did his job faithfully and was known to every drummer who stopped at

Dahlgren.

In

the hotel’s basement was the laundry, where all the sheets were ironed by

hand, the water system, furnace and a creamery, which was operated as a sideline

business by Mrs. Garrison’s uncle. The

local farmers would bring in their cream which was tested for its butterfat

content by Mrs. Garrison who, although scarcely in her teens, had passed the

examination to be a licensed cream tester.

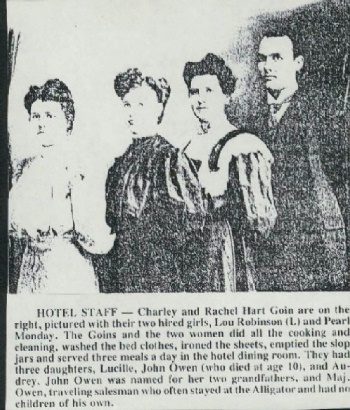

The

task of preparing meals for the guest was handled by the family and two hired

girls. The Alligator Hotel prided

itself on the abundance of its food. “Dad

always checked on the number of dishes that were to be served,” says Mrs.

Garrison. “If there weren’t at

least ten, we would have to open a can of corn or something to fill up another

dish.” The food was prepared on a

big Majestic coal range that held a huge reservoir of hot water.

In the summer, an oil stove was used because it made less heat in the

kitchen. Since there was no

electricity, kerosene lamps provided the light.

No

liquor was ever served on the premises. Mr.

Goin being a strict teetotaler. In

fact, anyone coming to the door smelling of spirits was asked to find other

lodgings. Rooms at the Alligator

coast about $1 per night with meals extra.

In the dining room there were three big tables—one for the family, one

for the traveling men and another for the local people.

Fay

Wham of Centralia, who grew up in Dahlgren, recalls that it was a rare treat to

eat at the hotel. “They had

wonderful food—and things like bananas. We

had home-canned peaches at home, but at the Alligator they had fresh fruit in

the winter.”

Mrs.

Wham also recalls the time the grocery store next to the hotel caught fire and

the local fire brigade answered the alarm.

Fearing that the flames would spread to the hotel, Mrs. Goin pleaded with

the crowd of onlookers to pray that the Alligator might be spared.

“Pray, fudge, we’d better fight fire,” retorted William Sneed,

Faye’s father, who had come to assist in extinguishing the blaze.

Fortunately, Rachel Going’s prayers were answered and the Alligator was

saved.

Charley

and Rachel Goin continued to operate the Alligator until 1920 when they sold the

hotel and moved to Mt. Vernon. “It

was never the same after the Goins left or after they paved the road,” says

Faye Wham. After years of muddy

roads that were impassable in wet weather, the first paved roads in the country

were a real delight. Mrs. Wham

recalls that she and her family would drive over to the new road that ran

between Mt. Vernon and Wayne City just for the sheer pleasure of riding back and

forth on the paved strip.

The

hard roads and the growing number of automobiles meant the end of small hotels

like the Alligator. Traveling men

could now drive from town to town and did not bother to spend the night at a

hotel near the depot.

The

livery stables went out of business and the car dealerships began to flourish.

One of these was owned by Charley Goin’s brother, who was known as W.

O. “Bill” Goin, or Uncle Omer to his family.

Bill Goin began his career in Bluford selling eggs, caskets and fresh

produce which he purchased locally from farmers.

He and his partner, Everett DeWiit, opened a Ford agency in Farina and in

the 1920s came to Centralia. Many

will recall that Goin lived in the big white mansion on Pleasant Street that

later became the Hudelson Baptist Children’s Home.

Their auto agency was located on the 100 block of S. Poplar.

Around 1934, Goin and DeWitt (who was married to Faye Wham’s sister,

Ava) both moved from Centralia to Jacksonville, Ill. and gave up the Centralia

agency.

The

Alligator Hotel has been gone for many years—a victim of paved roads and

progress. But in the minds of those

who remember it, the Alligator is grander than ever. Once can almost see the sweeping verandah with its swing and

wicker furniture, the drummers’ samples spread out on the long oak tables, and

most of all the alligators that gave the hotel its name and for many years were

Dahlgren’s chief claim to fame.

![]() Back

to Hamilton County

Back

to Hamilton County ![]() Back

to Hamilton County Miscellaneous

Back

to Hamilton County Miscellaneous